Answer of June 2021

For completion of the online quiz, please visit the HKAM iCMECPD website: http://www.icmecpd.hk/

Clinical History:

A 44 year-old male with known history with mixed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) and follicular lymphoma with multiple cervical lymphadenopathy was given 6 cycles of combined cytoreductive targeted therapy and chemotherapy. Two months after chemotherapy he developed fever, shortness of breath despite antiviral drugs and empirical antibiotics. Initial investigations show moderate leukopenia (WBC count 1.7 x 109/L) with mild neutropenia (1.3 x 109/L) and moderate lymphopenia 0.3 x 109/L). Urgent computed tomography (CT) was arranged in view of persistent fever and desaturation.

IMAGING FINDINGS:

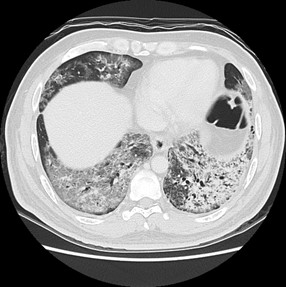

The chest radiograph shows bilateral lung infiltrates at left mid & lower zones, also right lower zones. No pleural effusion was evident.

The CT shows bilateral lungs predominate confluent ground-glass opacities, admixed reticular densities and some consolidative foci with lower zone predominance, associated subpleural sparing is noted. Several pneumatoceles are also present. There are no mediastinal or hilar lymphadenopathies. No pleural effusion is evident.

Overall features most likely represent atypical infection in an immunocompromised patient, and underlying PJP has to be considered.

DIAGNOSIS:

Pneumocystis Jiroveci Pneumonia (PJP)

DISCUSSION:

Pneumocystis Jiroveci is an atypical fungus that causes pneumonia in immunocompromised human hosts, particularly those with deficiency in cell-mediated immunity.

Radiographic findings of PJP are nonspecific, and as many as one third of infected patients may have normal radiographic findings. Volumetric high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) may be indicated in the evaluation of immunocompromised patients, and the results can be suggestive of PJP in the correct clinical situation, as demonstrated in our case.

Therefore, HRCT plays a central role in evaluating immunocompromised patients with new-onset lung disease.

Extensive ground-glass opacity is the principal finding in PJP, reflecting accumulation of intra-alveolar fibrin, debris, and organisms. Dark bronchus sign is often helpful to detect subtle or diffuse ground glass opacification, which is also evident in our case. These are predominantly involving perihilar or mid zones. Exception exists when the patient is on prophylactic aerosolized pentamidine, then an upper zone predilection will be seen.

With more advanced disease, septal lines with or without intralobular lines superimposed on ground-glass opacity (crazy paving) and consolidation may develop. Relative subpleural sparing is evident.

Pneumatoceles are reported to present in about 30% of cases, they show variable shape, size, and wall thickness. They are associated with an increased frequency of spontaneous pneumothorax

It is worthwhile to know that pleural effusions and lymphadenopathy are uncommon.

Main imaging differentials include infection such as viral pneumonitis or interstitial lung disease (e.g. lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis (LIP)). Viral pneumonitis can have variable findings and some of the viral infection (such as Cytomegalovirus or Influenza infection) may have overlapping features of ground-glass opacities and interlobular septal thickening, but the presence of pneumatoceles is uncommon. COVID-19 infection typically shows subpleural, lower zone predominant ground-glass opacities and interlobular septal thickening without pneumatoceles. As for LIP, the cysts are typically peribronchovascular distribution. There could also be the presence of centrilobular or subpleural nodules which are typically absent in PJP. For tuberculous infection, presence of cavitary lesions and tree-in-bud nodules in the upper zone of lungs are expected in case of reactivation.

Although it is classically an AIDS-defining illness in Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) patients, it is important for radiologists to recognize that the PJP among patients without HIV infection presents with a different clinical and imaging profile. First, the incidence of PJP among persons without HIV infection exceeds that associated with HIV infection. Second, they typically present with acute illness associated with severe hypoxia and result in rapid respiratory deterioration and respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, instead of subacute presentation. On CT, there is greater extent of ground-glass opacities, and lung consolidation is more commonly observed & tends to develop more rapidly, reflecting pulmonary damage from the host immune response. A more significant mortality rate was reported in non-HIV infected patients (34-39%) than HIV-infected patients (6-7%).

Confirmation of the diagnosis requires identification of organisms in sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

Confirmation of PJP can be difficult in patients without HIV infection because of the much lower burden of organisms.

Most patients with acute infection are treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (co-trimoxazole or TMP-SMZ), combined with corticosteroids in patients with moderate to severe infections. The same agent may be used as prophylaxis.

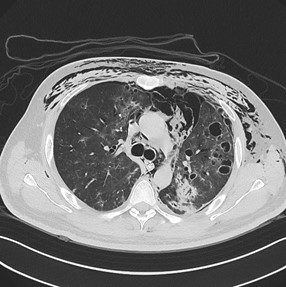

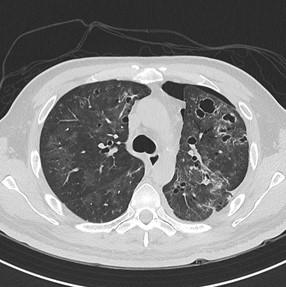

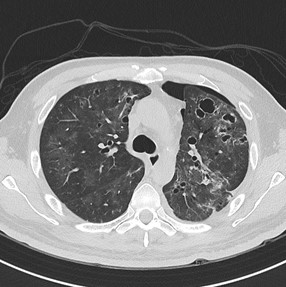

In our case, no PJP prophylaxis was given prior to the admission. Subsequent bronchoalveolar lavage was positive for Pneumocystis pneumonia polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Nasopharyngeal sample for COVID-19 virus was negative. Anti-HIV antibody was tested to be negative. He was treated with intravenous Cotrimoxazole and steroid. Potential risk factors attributable to PJP was immunocompromised state with lymphoma and profound leukopenia and lymphopenia. The disease was complicated with left pneumothorax requiring chest drain insertion but with persistent air-leak and follow-up CT 2 weeks after (see selected image below) showed extensive surgical emphysema, left pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum and gradual resolution on CT 4 weeks after (see selected image below). There is interval decreased ground-glass and consolidative change but persistence pneumatoceles on these CTs.

This case highlights how PJP presents in non-HIV patients and the crucial role for radiologists to identify PJP in the correct clinical setting with the classic imaging findings on CT.

CT after 2 weeks (a) (b)

CT after 4 weeks (a) (b)